Post America Invents Act — Inside the “On-Sale Bar” of 35 USC §102

The Constitutional right to obtain a patent is subject to certain limitations, including that an inventor may be barred from obtaining a patent if the invention was sold or publicly disclosed prior to filing the patent application. The America Invents Act (“AIAâ€) changed the statutory language of 35 U.S.C. section 102 regarding when a prior disclosure may bar an inventor from receiving a patent.

My article discussing this was published on Law360.com. The text of the article is set forth here:

Section 102(a) is clear and appears to provide a bright line test for determining when a disclosure precludes an applicant from receiving a patent. Section 102(b), however, sets forth exceptions that blow a cloud of smoke over the clarity of Section 102(a).

THE GRAY AREA

Section 102(a) provides clear rules for determining activities that may bar an inventor from getting a patent: the invention was described in a patent, printed publication, or was in public use, or on sale before the filing date of the patent application.

However, section 102(b) provides exceptions to 102(a). Under section 102(b)(1), certain disclosures made within one-year prior to filing a patent application may or may not bar the applicant from getting a patent. In addition, under 102(b)(2) disclosures made at any time in specific patents or patent applications may or may not bar the applicant from getting a patent.

THE AIA DOES NOT DEFINE “DISCLOSUREâ€

All of the exceptions found in section 102(b) are identified as “disclosuresâ€. Clearly, the word “disclosure†is extremely important. However, Congress did not define “disclosure†in the AIA. And, the word “disclosure†is not used in Section 102(a).

Congress wrote the statute with vague and confusing language, leaving it up to patent examiners at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (PTO) to interpret and implement the statute. Patent examiners often are not attorneys, and it is not their job to interpret obtuse statutory language. But, being on the front lines, PTO had to come up with some rules to deal with this statutory mess. Therefore, the Manual of Patent Examination Procedure (“MPEPâ€) provides a working definition of the word “disclosureâ€, stating:

“[T]he Office is treating the term “disclosure†as a generic expression intended to encompass the documents and activities enumerated in 35 U.S.C. 102(a) (i.e., being patented, described in a printed publication, in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public, or being described in a U.S. patent, U.S. patent application publication, or WIPO published application).†See, MPEP 717.

DISCLOSURES DURING THE GRACE PERIOD — SECTIONS 102(a)(1) and 102(b)(1)

AIA Section 102(a)(1) seems straight-forward and clear, and provides:

(a)Novelty; Prior Art. — A person shall be entitled to a patent unless –

(1) the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention; …

Section 102(b)(1) provides exceptions to this rule, stating that certain disclosures made within one year of filing the patent application will not preclude an inventor from getting a patent. This time frame is often called the “Grace Periodâ€.

In other words, although section 102(a)(1) says all public disclosures made prior to filing a patent application will bar the patent, section 102(b)(1) says that some disclosures made within one-year of filing will not bar the patent. If a 102(b)(1) exception applies, then the inventor may still be entitled to a patent.

In particular, under section 102(b)(1) if the inventor, or a joint inventor, publicly disclosed the invention within one-year prior to filing the patent application, the patent may still issue. These inventor-initiated public disclosures will not bar the applicant from receiving a patent.

SUBJECT MATTER DISCLOSURES – SECTIONS 102(a)(2) and 102(b)(2)

The AIA changed the U.S. from first-to-invent to first-to-file. The legislative history of the AIA shows that the exceptions found in Section 102(b)(2) were written to deal with the situation where an inventor, or joint inventors, previously filed a patent or patent application that disclosed an invention that is also disclosed in a subsequently-filed patent application. As explained in the Congressional Record, the “first-to-file system†may be more properly characterized as a “first-to-disclose systemâ€.

Section 102(a)(2) states:

(a)Novelty; Prior Art. — A person shall be entitled to a patent unless – …

(2) the claimed invention was described in a patent issued under section 151, or in an application for patent published or deemed published under section 122(b), in which the patent or application, as the case may be, names another inventor and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention.

Section 102(b)(2) discusses “subject matter†disclosures, and provides that even if a pre-existing patent or patent application discloses the subject matter of the applied-for-invention, an applicant may still be entitled to a patent.

In particular, section 102(b)(2) provides that an inventor/applicant may still be entitled to a patent if: (i) the subject matter disclosed in the pre-existing patent or patent application was obtained directly or indirectly from the inventor or a joint inventor; (ii) the subject matter disclosed had been publicly disclosed by the inventor or a joint inventor; or (iii) the subject matter disclosed and the invention claimed by the applicant were owned by the same person or subject to an obligation of assignment to the same person. Thus, there must be a nexus between the inventor(s) claiming the applied-for-invention and the inventor(s) of the pre-existing subject matter disclosure.

Section 102(b)(2) does not provide any time limit on the subject matter disclosures found in pre-existing patents and patent applications, these pre-existing patents and patent applications may have any publication date. They are not limited to publications made within one-year prior to the filing date of the patent application.

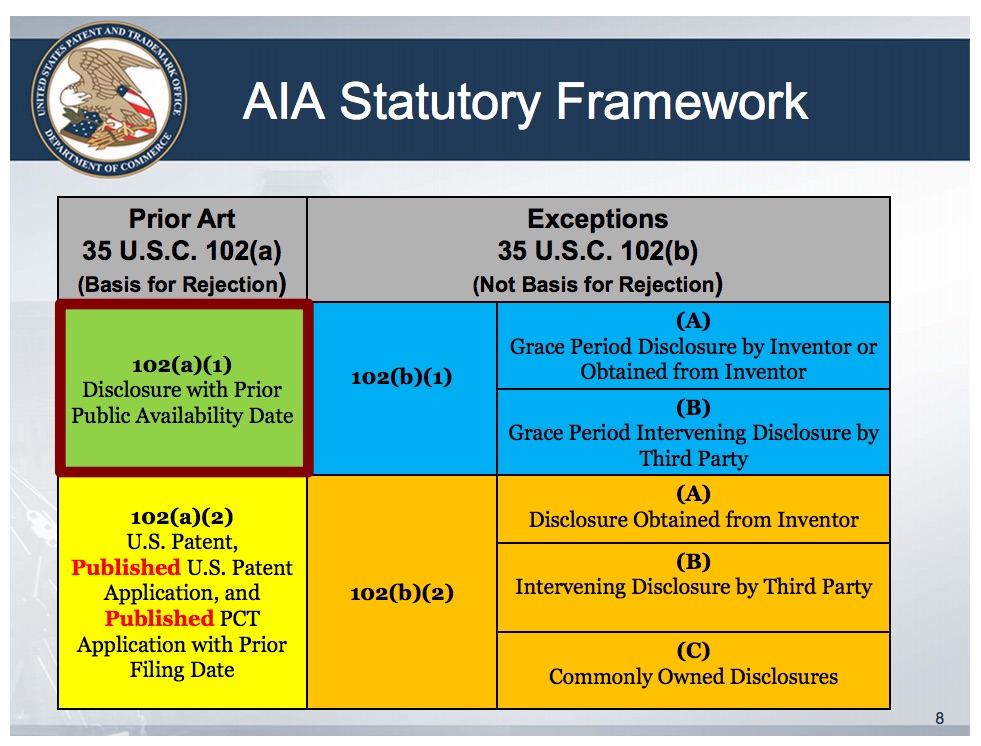

U.S. PTO CHART

In addition to providing a working definition of “disclosure, the PTO provided a chart in of the exceptions found in 102(b). This chart is a nice summary of some complex concepts found in Section 102.

The chart shows that there is the statutory redundancy between Sections 102(a)(1) and 102(a)(2) – a published patent or patent application (102(a)(2)) is the same as a public disclosure (102(a)(1)). It appears that this redundancy was to keep the exceptions in line; that is, the exceptions found in 102(b)(1) relate to 102(a)(1), while the exceptions found in 102(b)(2) relate to 102(a)(2).

LIMITED CASE LAW

There is limited case law discussing 35 USC § 102 under the AIA since the statutory changes are relatively new and are working their way through the court system.

One case, MyGo, LLC v. Mission Beach Industries, LLC, U.S. District Court, S.D. California, Case No. 3:16-cv-02350-GPC-RBB (January 11, 2017) discusses post-AIA 35 USC §102(a) and the exceptions found in 102(b).

This case started when both MyGo and MBI filed patent applications at almost the same time, with MyGo filing first by about a month, and being published first. During prosecution of MBI’s patent application, MyGo submitted its published patent application into the record of MBI’s patent application, asserting that its published patent application was prior art. PTO subsequently rejected all of MBI’s claims as being anticipated by the prior art reference, and MBI abandoned its patent application.

However, the story was not over. MBI continued to sell its product, and MyGo sued for infringement of its issued patent. MBI asserted a counterclaim that MyGo’s patent was invalid under 102(a)(1), alleging that MBI used its invention on a public beach prior to the date MyGo filed its patent application.

The court analyzed this and found that MBI stated a valid claim, even if MBI’s public use was during Grace Period found in 102(b)(1). Public use by MBI is not use by the inventor (MyGo), and therefore the exceptions found in 102(b)(1) are not relevant. And, although the court did not discuss this, the exceptions found in 102(b)(2) also did not apply — there was no disclosure by MyGo to MBI. Therefore, the court denied MyGo’s motion to dismiss MBI’s counterclaim, and MBI is pursuing its attempts to invalidate MyGo’s patent based on MBI’s prior use.

CONCLUSION

The AIA changed the United States from first-to-invent to a first-to-file country. In doing so the AIA changed the rules regarding when a public disclosure, use, or sale may bar a patent applicant from receiving a patent. The AIA provides a one-year grace period for public disclosures made by an applicant in the year prior to filing a patent application. These disclosures will not bar an applicant from receiving a patent. The AIA further provides that subject matter disclosures made in published patents or patent applications will not operate to bar an applicant from receiving a patent if there is a nexus between the applicant and the prior patent or patent application. The AIA also changed previous interpretation of the rules, and now provides a clear rule that disclosures made in private before the filing date of a patent application will not bar the applicant from receiving a patent.